I'm not going to focus on food-centred economies today, as was promised at the end of my last entry (sorry!). But, if you are interested in this, check out these great LETS (Local Exchange Trading Systems) links!

I'm currently finishing up two of my Human Environment 400-levels, Environmental Management and Urban Ecology, and I'm finding some really interesting links between them. So instead I'm going to address these links through a discussion about urban agriculture's potential in contributing to sustainable urban communities. It seems a critical way for urban planners and environmental managers to cooperate.

There are a few things that need to be made clear before I get to the crux:

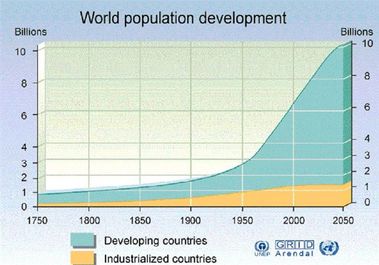

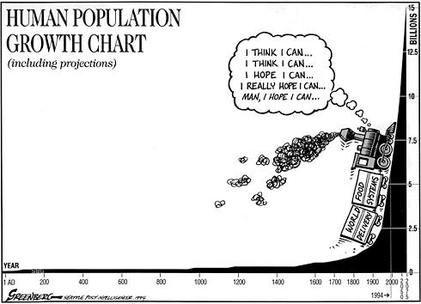

Since the industrial revolution, the global human population has been growing exponentially - from about one billion people to over six billion people today. Think about that! It took thousands and thousands of years for the human population to reach just one billion people, and only the last two hundred for the population to increase by five billion people!

I'm currently finishing up two of my Human Environment 400-levels, Environmental Management and Urban Ecology, and I'm finding some really interesting links between them. So instead I'm going to address these links through a discussion about urban agriculture's potential in contributing to sustainable urban communities. It seems a critical way for urban planners and environmental managers to cooperate.

There are a few things that need to be made clear before I get to the crux:

Since the industrial revolution, the global human population has been growing exponentially - from about one billion people to over six billion people today. Think about that! It took thousands and thousands of years for the human population to reach just one billion people, and only the last two hundred for the population to increase by five billion people!

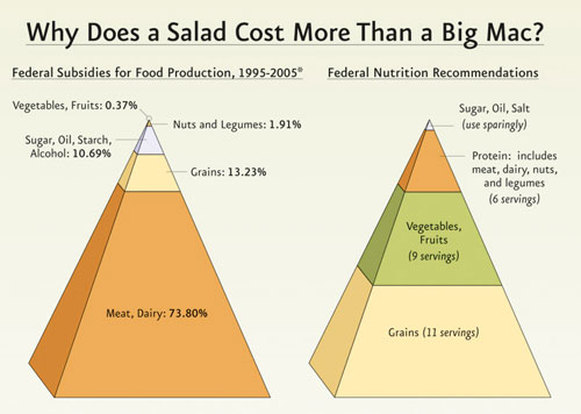

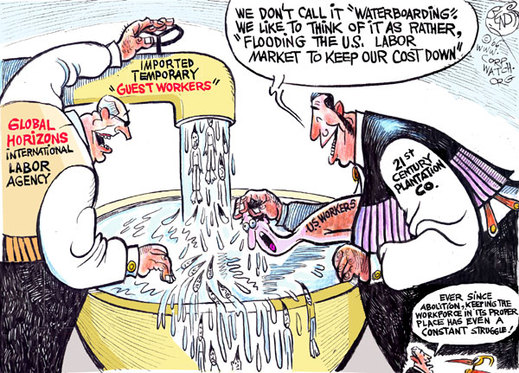

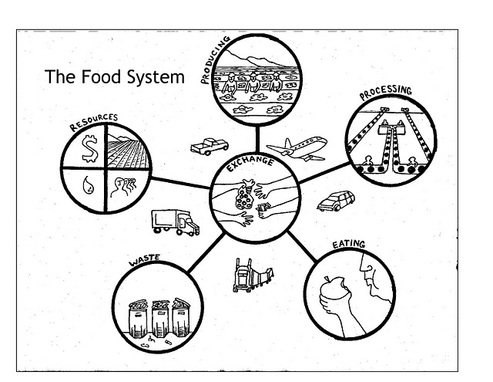

All these people (along with our cars, homes, and insatiable consumption habits) put A LOT of pressure on the planet's natural resources, and release TONS of waste for the planet to absorb. And think about what this means for the food system!

Over half of the world's population is concentrated in urban centres, and are indirectly interacting with the environment. Because urban dwellers are living in a human-made world, and not directly experiencing the effect of their activities on the environment, a city-nature divide has formed in many people's minds. This mental divide causes people to see these two as separate - the city as an insular environment, not affecting the "pristine" nature so many admire, and nature as external to the city, capable of being overcome by technological advancements.

An interesting concept in urban ecology is that of the city as an organism, relying on inputs from nature and releasing outputs into nature. This cycle of consumption and waste production is called the urban metabolism. With today's global economy, enabling us to consume natural resources from all over the planet, we are experiencing global problems - the most dire of which is global climate change.

There are ways for us to lower cities' contribution to global climate change, and civic ecology is one of them. My simple definition of civic ecology is, "the combining environmental management with community building." Basically, it's about groups of urban citizens getting together to improve the ecology of urban spaces, whether it be through watershed restoration, community forestry, or community gardening.

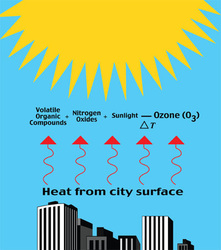

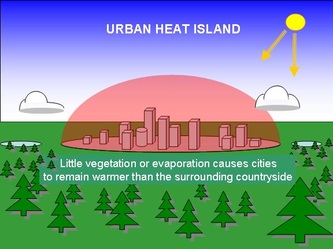

Community forestry and gardening increase the amount of green space in cities, which lowers the urban heat island effect.

An interesting concept in urban ecology is that of the city as an organism, relying on inputs from nature and releasing outputs into nature. This cycle of consumption and waste production is called the urban metabolism. With today's global economy, enabling us to consume natural resources from all over the planet, we are experiencing global problems - the most dire of which is global climate change.

There are ways for us to lower cities' contribution to global climate change, and civic ecology is one of them. My simple definition of civic ecology is, "the combining environmental management with community building." Basically, it's about groups of urban citizens getting together to improve the ecology of urban spaces, whether it be through watershed restoration, community forestry, or community gardening.

Community forestry and gardening increase the amount of green space in cities, which lowers the urban heat island effect.

Increasing green space has so many natural advantages: increases evaporation (has a natural cooling effect), absorbs carbon dioxide (lowers greenhouse gas emissions), purifies air, provides storm water control, and the list goes on. Not only that - green spaces, especially in the form of community gardens, increases all forms of community capital. Check out this great elaboration of community capital while thinking about the context of community gardening:

It's so simple that I don't think any further explanation is required!

If you live in Montreal and want to get involved in some community greening (and become environmental stewards!), check out the Urban Ecology Centre. And, of course, if you're a Concordia University student, get involved with the Concordia Food Systems Project!

See you there! :)

(Click on the pictures to see where they're from.)

If you live in Montreal and want to get involved in some community greening (and become environmental stewards!), check out the Urban Ecology Centre. And, of course, if you're a Concordia University student, get involved with the Concordia Food Systems Project!

See you there! :)

(Click on the pictures to see where they're from.)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed